This article was published in Blueprint magazine in 2011 (too lazy to check which issue exactly). It was then re-published by John Boardley in his Codex magazine, albeit slightly edited. I re-re-publish it here because the discussion about digital kitsch and appropriate metaphors has just come up again, mainly because Apple’s OS Lion now also features faux leather and adds pseudo-physical features like animated turning of pages to the interface which first appeared on the iPad, a populist device, not a computer that the likes of us depend upon for work.

The list of available fonts on iOS mentioned at the end may be out of date, but you’ll get the message. Since I wrote this, the new iPad has appeared, featuring the amazing Retina high-resolution screen. Its sharpness suddenly shows up the flaws in typefaces. To me – an old person – this reminds me of the discussion we had when photosetting took over hot metal type in the 70s. And everybody makes the same assumptions again. Mostly the wrong ones, looking for a solution in technology instead of design.

“A typographer who hasn’t found the appropriate typeface may not have decreased the informational value of a text, but gave up the opportunity to considerably increase its effectiveness.”

Thus wrote G.W. Ovink, Dutch typographer and historian, way back before he knew any other media besides paper.

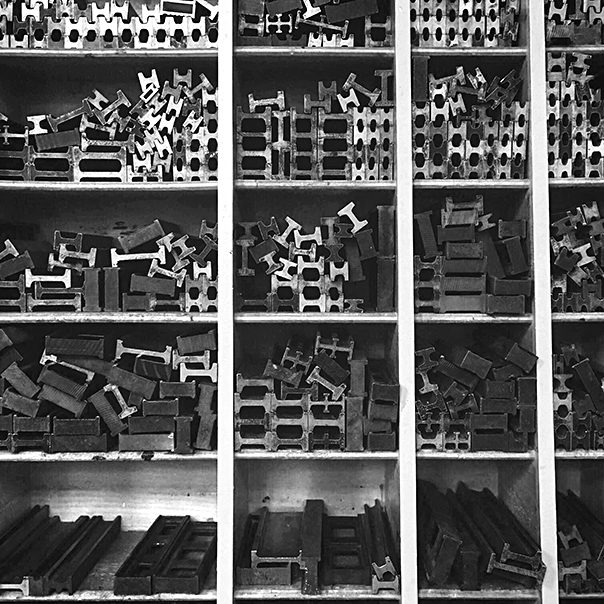

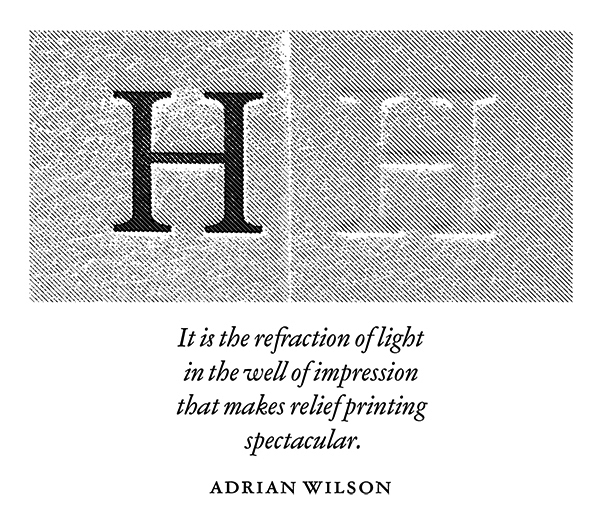

Every medium has always had constraints for the type that goes with it. Whether you design a newspaper, a poster, a stamp or a website: you have to consider the technical environment, the reader, the client, the content. As the surfaces of substrates used for printing got smoother, the resolution of type went up along with it. If you look at a Gutenberg Bible through a magnifying glass, you’d never believe the craters, bumps and blotches that look like gorgeous letters from a safe reading distance. Bright and shiny, smoothly coated paper for high-quality offset printing requires the letters to be sharp and well-defined, even though the human eye doesn’t like too much contrast. Technology, being what it is – a means to promote itself if not mankind – kept providing more resolution and thus invisible detail than we ever needed. Once printing could hardly be more refined, along came the Cathode Ray Tube, and all the high definition that the suppliers of typesetting and printing equipment had declared not only inevitable but vital, was broken down into crude bits of colour, red, green and blue only. Type suddenly looked like Lego bricks when compared to the refinement a printer like Bodoni had been capable of at the beginning of the 19th century, long before photosetting and offset printing, let alone coated stock.

The web has always just been bad paper. Now it’s starting to look like good paper and designers will have to treat it as such. But as always at the beginning of a new paradigm, we have to imitate the old one while we get used to the new possibilities that people over a certain age always consider a challenge. Apart from what technology will allow us to do, there are physical laws – our eyes, our brain, light, contrast; we cannot ignore those if we want to communicate. Cultural parameters like reading habits, literary culture (or lack of) – our deeply embedded fear of change, all these give an excuse to imitate the old, even though there are no technical reasons to do so. But we read best what we read most.

Every new medium raises the same questions. Things which were thought mature in one media will take a while to mature in a new one. Look at the new electronic books, particularly those on Apple’s amazing iPad: a book is presented as a reproduction of the traditional stack of bound pieces of paper. Going from one page to the next is accompanied by an animation of it being turned, even with the sound of paper being rustled. While you keep thumbing pages, however, the stack stays equally thick on either side, turning the metaphor into a lie, into digital kitsch. It feels wrong and it is wrong. Metaphors are useful because we do not really want to know what goes on in the digital maze under the bonnet that the operating system hides. Superfluous visual noise doesn’t make the reading any easier, it just presumes that we’re too stupid to notice the difference between a stack of glued paper and a battery-driven piece of plastic. If people really wanted to emulate the whole physical experience, why not give us the musty smell of old books, the scent of printing ink?

Worse than those misguided and patronizing metaphors is the fact that publishers can no longer decide which typeface their text is set in. Apple provides just five (Baskerville, Cochin, Palatino, Times, Verdana), and only one of them (Palatino) can be considered a book face suitable for reading on a screen. Somehow, the dichotomy seems weird between cool aluminium shapes, high-tech displays and amazing technology on the one hand, and wooden bookshelves on the other, as a metaphor for an online bookshop which provides books that look older on screen than they do in the real world. Perhaps the individual design departments responsible should talk to each other? The industrial designers certainly seem to be ahead of the User Interface people at Apple.

Still, while electronic books have a way to go (the Kindle is actually a little further ahead in typographic matters), there are signs that the web will soon allow the same degree of typographic refinements that we’re used to on traditional paper. Not only can we use every existing typeface to be displayed in a browser, but new mark-up languages will give us typographic treats like ligatures, small caps and old style figures that printers in the 15th century developed for their books which we still consider benchmarks today. If only somebody could invent a battery that lasted as long as paper does.